In 2014, ISS, a facility management company and one of the world’s largest employers, launched a gamified mobile application for employees called Share@ISS. The application engages ISS employees to be proactive by incentivising the sharing of ideas for potential facility improvements that they encounter in their daily work. After a three-month pilot project ISS saw a doubling of proactive employees at the sites where the application was tested.

Share@ISS provides a case study that demonstrates the advantages of gamification and digitalisation, and provides valuable insights into how users perceive gamification effort that are designed to support their existing workflows.

As anthropological investigation identified ISS employees’ workflows, internal processes and associated behaviours and was the foundation of ISS’ gamified platform. In this paper we examine how it is possible to create a sharing culture through a platform that derives its value from game elements and social features, but also simply makes work easy and more effective. With a clear business benefit found in incentivising ISS workers to become more proactive in their sharing of opportunities, we present the application of gamification as a means by which to make the work of employees more engaging while also incentivising behaviours that are in line with the commercial side of ISS’ business.

After a positive pilot project, the application has turned into a popular work tool within the organization and continues to grow. It is already in use by ISS in Denmark, UK, Israel, Sweden and the United States. While Share@ISS is in continuous development, the data collected demonstrates the positive effect of the application on user behaviour as well as diversity in how users perceive of workflow supporting gamification initiatives.

1 Introduction

1.1 Pro activity

Let’s gamify this paper and start out with a little role-play.

you’re a cleaning lady. You’ve just gotten off the bus and you’re walking up to the headquarter of a global IT manufacturer. They’re your client. You’re working for the global facility service company ISS and together with your colleagues you make sure that the IT manufacturer can focus on what they’re best at – manufacturing IT products – by taking care of facility services such as cleaning, catering and maintenance. Though cleaning the floors and restrooms can be a bit tedious you actually like your job. Your colleagues are good friends, the pay is decent and the career options are good within the company. Today’s cleaning isn’t the easiest. You probably stayed an hour too late at your friends birthday party last night and on top of that, your boss, the site manager, asked if you could finish up 15 minutes early, as the catering supervisor needs to brief everyone on something. As you’re about to enter one of the conference rooms on your cleaning route you notice that the door know has gone loose. What do you do? Should you tell someone? You do a quick calculation: pros: you know it would be a good service to notify your site manager so he can ask the client if ISS should fix it. Cons: you’re a bit tired, you’re a little busy, and you’re not sure where the site manager is right now. You could write a not; however you’re not sure what happened last time you put a note on his desk about something that needed fixing… too many cons.

Most of us probably recognise these moments where we stop for a second and ponder if we should do that little extra or just continue doing what’s expected. It was a wish to influence these types of moments that started the gamification project at ISS.

1.2 A key ingredient to premium service

ISS is, with more than 500.000 employees one of the world’s largest employers. With 114 years of experience they’re a renowned and solid name in facility services around the globe. More than anyone, they know that a key ingredient to providing premium service is to be proactive. It’s simply a fundamental part of what keeps their clients happy – that the client can focus on what they’re best at – while ISS takes care of facility issues before the clients notice themselves. However, ISS also knows that being proactive is a behaviour amongst employees that you can’t take for granted nor easily recruit or incentivise. In their efforts to develop and drive a culture where proactivity is recognised, ISS already has a global incentive program where you nominate fellow colleagues who’ve shown an outstanding example in generating value for the client. As this resembles more traditional programs, like getting a medal in the military for a significant and outstanding performance, it became apparent that there was still room for incentivising on a more “micro behavioural” level; to focus on those everyday moments where someone considers reporting that loose doorknob.

1.3 A clear business case

Focusing on a micro behaviour that realistically tends to happen more often, rather than extraordinary achievements, makes the business case quite obvious – especially when you’re dealing with more than 500.000 employees. Also, not only is proactivity a service essential that keeps the client happy, it’s also a natural part of the commercial side of the business; if the client gives ISS a go on fixing that doorknob it naturally adds to the revenue. This perhaps makes it less of a surprise that it was Thomas Zeihlund, a CFO at ISS, who sensed a potential when he first learned about gamification. It was clear that there could be a significant business potential and an opportunity for providing better service for the clients in motivating proactivity on a micro behavioural level amongst employees by making it motivating and maybe even fun for them to find potential facility improvements. ISS invited Orchard MBC, an agency specialised in micro behavioural change, gamification and digital design, to do a pilot project that would answer the question: Can we motivate our staff through gamification to be more proactive by making it fun and easy to report potential facility improvements?

2. The process

2.1 Ethnographic research

In an effort to include different cultures and facility types, the Orchard team invites five ISS locations to participate in the pilot project; two in the US, one in the UK, one in Israel and one in Denmark. Parallel to refining the conceptual approach to the solution, a series of ethnographic field visits were carried out. The ethnographic approach made it possible to get into the mindset of ISS ground level employees and understand practices around reporting potential facility improvements (Eriksen & Murphy 2008; Hammersley & Atkinson 1983). During the visits, the team conducted interviews with the site management as well as participant observation with a range of personnel, including custodial and maintenance workers.

The field visits provided the team with an in-depth understanding of several central questions such as; under which circumstances is pro-activity happening and what are the reasons when it’s not? How does an idea for an improvement travel from person to person and into work order systems until it’s fixed? Is it even realistic in a practical sense to motivate a busy cleaning lady to pull out a smartphone and share an idea for an improvement she sees one?

2.2 The importance of feedback

One of the most important initial findings, that also had a notable impact on the subsequent application’s concept and design, was that an absolute essential circumstance in order for the proactive behaviour to happen was that feedback also happened. Those who experienced a strong sense of purpose, for example through colleagues or clients recognising their extra effort, were indeed proactive and took pride in performing that behaviour – positive feedback was important to them. Several works support this view (eg. Burke 2014; Pink 2009) and shows how finding purpose in certain activities will increase motivation in performing that activity. Those who weren’t as pro-active had less sense of purpose, as they had usually tried being proactive but hadn’t experienced feedback as a result. From a gamification standpoint, one could likely consider various graphic responses, progress bars, leveling up etc. for providing feedback to employees (Werbach & Hunter 2012). However, a key finding was that many of the employees were specifically driven by the feedback from their peers. There was nothing more satisfying for a maintenance worker than to gather a few colleagues to discuss an issue and how to fix it. This wasn’t just happening offline; the facility managers from sites across Israel had simply set up a group chat on WhatsApp, as they needed a place for discussing ideas and giving each other feedback – but most of all to socialise.

For most of the staff, attempts to simply replace the social feedback and interaction with something like a virtual badge would be a straight up insult. “So you’re gonna give me a bloody gold star for doing my work?” A maintenance worker in the UK asked with a twinkle in his eye. This remark stayed with the team as a constant reminder of how delicate a task it is to apply play to other people’s work lives. Your best intentions can fail so miserably if you don’t make sure you get into the mindset of your future players – are they motivated by the intrinsic factors such as doing their job well, or by the extrinsic “Bloody gold star”? Having too much focus on adding points or extrinsic rewards is a risk as this may shift the focus from the real purpose of the activity and in extreme cases make users “addicted” to the reward rather than enjoying the activity itself (Deci & Vansteenkiste 2004; kohn 1999). This was a crystal clear reminder to avoid managerially-imposed mandatory “fun” (Mollick & Rothbard 2014) and instead design a solution where gamification was subtle and optional.

The team learned that a social component should be central in facilitating peer-to-peer feedback, as getting recognition through comments and likes on the ideas for improvements would be a motivational driver for many. Initial ideas about gamifying that an employee simply reports the ideas to the manager would therefore hardly do the trick. The ideas needed to be shared with the trusted colleagues on site, with the site manager invited to this “Employees’ forum” rather than employees reporting to the boss. This is why it was decided to design a shared feed, in some ways similar to Instagram’s, with pictures of ideas for facility improvements that all ISS employees on the site could see and interact with. The UX was therefore reworked in an effort to master the balance of being a useful work tool in itself, where you could share an idea in no time but also have a gamification side to it that wouldn’t disturb those who just wanted to use it for quick and easy reporting. This also influenced the way the Orchard team eventually introduced it to the pilot users; as a work tool that they were welcome – but not obliged – to use. A work tool that could balance the intrinsic and extrinsic motivators, providing the user with a choice when using the application (Deci & Vansteenkiste 2004).

2.3 Gamifying a fun core

During the field visits the team saw that many of those employees who were proactive actually found joy in finding these potential facility improvements as they went about their daily work. It was as if some of them practiced the famous movie quote from Mary Poppins (1964) “In every job that must be done, there is an element of fund. You find the fun and ‘snap’, the job’s a game.” It was almost like a scavenger hunt, but just very single-player based. This finding was extremely important to the concept development as it underlined that the team was onto something if the core of what they wanted to gamify had a fun element to it already. This also meant that it was possible to gamify not only a desired behaviour but also a specific work process and that finding these improvements and sharing them could be the game itself. Whatever ideas that were about creating a fun game that perhaps taught employees how or why to find facility improvements suddenly seemed silly when it was possible to gamify the actual work process.

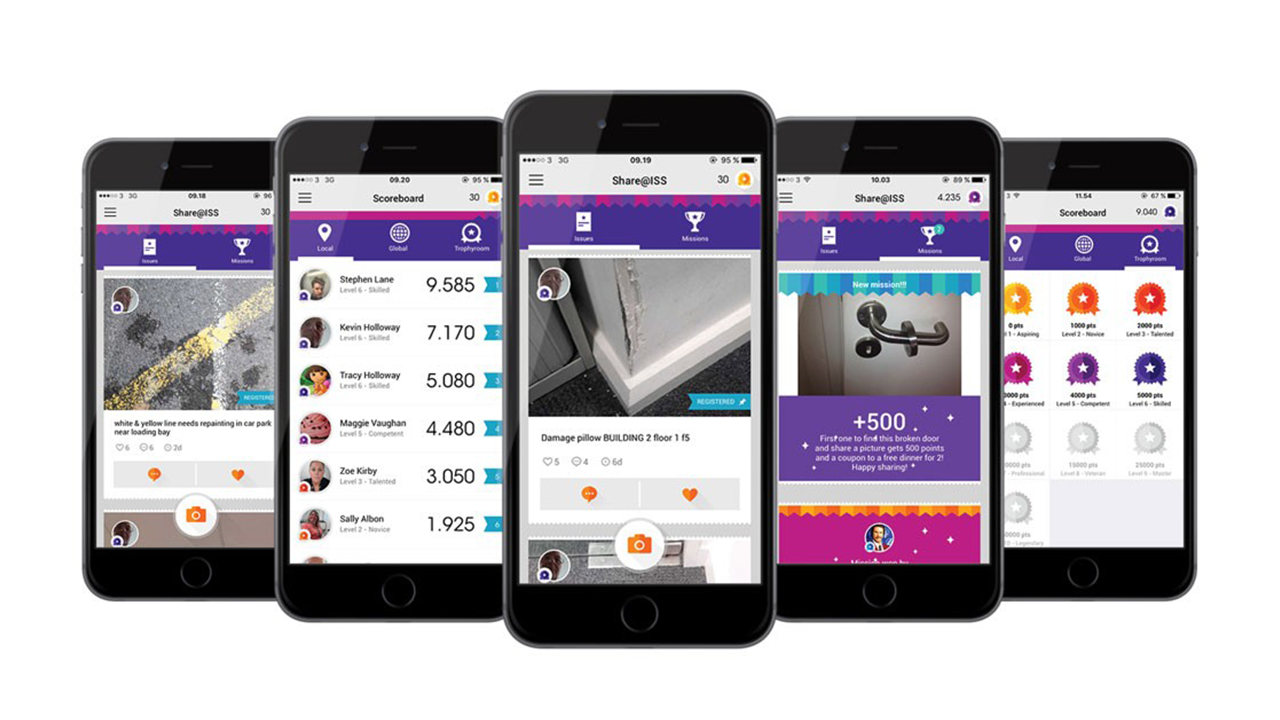

From here on the conceptual focus was on gamifying and incentivising the various steps in the work process. So naturally, in the app you gain points by sharing an idea, points when the manger registers the idea and even more points of the idea is carried out. As we know from the game design literature (eg. Salen & Zimmermann 2004), how points are gained usually indicates what the game is all about, indicating the rules of the game, but here specifically they also had a function in communicating and rewarding that the “work order” had progressed in status and thereby fuelling a sense of purpose; “Oh, someone went along with getting that door know fixed!” Early in the pilot phase the team saw what they expected to see, some picked up on the game side of the app and others didn’t. some were very vocal about it: “I’m second on the leaderboard, so come and get me!” as a service navigator in Sweden expressed proudly, and some were less vocal like the maintenance worker in California who indicated that their colleagues in Texas must be cheating since they had that many points.

2.4 Share!

These finding moved the Orchard team from an initial understanding of a need to gamify reporting to a concept of gamifying a social sharing of ideas. And the desired behaviour therefore also crystallised itself to sharing ideas, which offered a straightforward name for the application by simply using the imperative clause: Share!

2.5 Global gamification

ISS were quick to let the team know that they are indeed a global organisation and therefore cultural differences are significant. Not just across regions, but also on the specific location since you’ll often find immigrants from all corners of the world getting their first job opportunity in a new country with ISS. This multicultural reality had a direct influence on the design and gamification. First of all, it became a goal in itself to avoid as much text as possible as the users would naturally speak different languages, but also because the team was advised that there would be several illiterate employees. Completely avoiding text wasn’t possible but the designers put an effort into creating an icon-based navigation, guiding users with an app-tour, introducing the interface when the user opened the app for the first time and using design references from other popular apps, so that if they knew those apps they would pick up on this one more easily. The field visits revealed the site manager as an essential player in the game. The site manager and assisting supervisors on larger facilities are the ones who know If an idea for an improvement should just be fixed straight away as it might be covered by the contract with the client, or if the client should be presented with an offer. The site manager appeared to have a rather challenging role in guiding the staff in what potential facility improvements to look for. Say, if a couple of employees had suggested paint jobs to cover those black marks on the walls from the chairs in the meeting rooms and the client didn’t want to prioritise that expense right now, he should then put quite an effort into both appreciating the proactive effort but also inform all staff on site not to suggest more paint jobs right now, but to please keep looking for other ideas. This can be a challenge on a busy day.

The insight of the facility manager as kind of a playmaker in the “improvements hunt” together with the multicultural challenge gave birth to the idea of having missions as one of the central game elements. Not only can the manager initiate missions to add fun challenges to the game and through that guide everyone to, for example look for potential energy saving improvements, but they can also incentive employees by setting up rewards in line with the local culture. This ensured that there was flexibility in the perceived value of the reward and the motivation for achieving the reward (Pihl 2013). This gave the Israeli cleaning supervisor the option to include a more tangible reward like the pad breakfast at a local restaurant for the whole family, that earlier had shown itself to be very appreciated by the winning Ethiopian cleaning ladies with their larger immigrant families. By contrast, another manager in Denmark might choose an intangible reward if he felt that would trigger competition.

2.6 A lean Startup approach

Unsurprisingly, it proved difficult, if not impossible, to ask the employees- the future players- if the game would be fun. How would they know? On the basis of that- and for financial reasons- it made sense, as it often does, to apply a lean startup approach (Ries 2011) to the process. It was therefore decided to build a more basic version of the tool with just the concept critical features on order to be able to release it sooner and thus quickly learn what worked and what didn’t and then adjust. What if the employees found it fundamentally inappropriate or silly to gamify their work? What if it turned out that they disliked competition and the team spent several weeks programming an advanced leaderboard? It made sense to create a minimum viable product (MVP) – or could we call it minimum viable gamification? – in order to learn quickly what resonated with the users and what didn’t. what they found useful or motivating could then quickly be developed further, and those features that didn’t provide value could be skipped without looking back on months of wasted design and programming.

2.7 Development and testing

In the spirit of the MVP, a mobile application was developed for Android only – after a series of iterations on the concept, UX and design. Following a 3-month development period the mobile application together with a web application for the facility managers was soft launched at one of the sites for a 2-week period followed by a 3-month pilot testing period on all five locations. The users were unboarded with assistance from the team and weekly status meeting were conducted with the facility managers as they played a central role in managing the suggested improvements, providing feedback to the employees and generally supporting a culture where sharing ideas is appreciated. If site managers didn’t play along, the game would end.

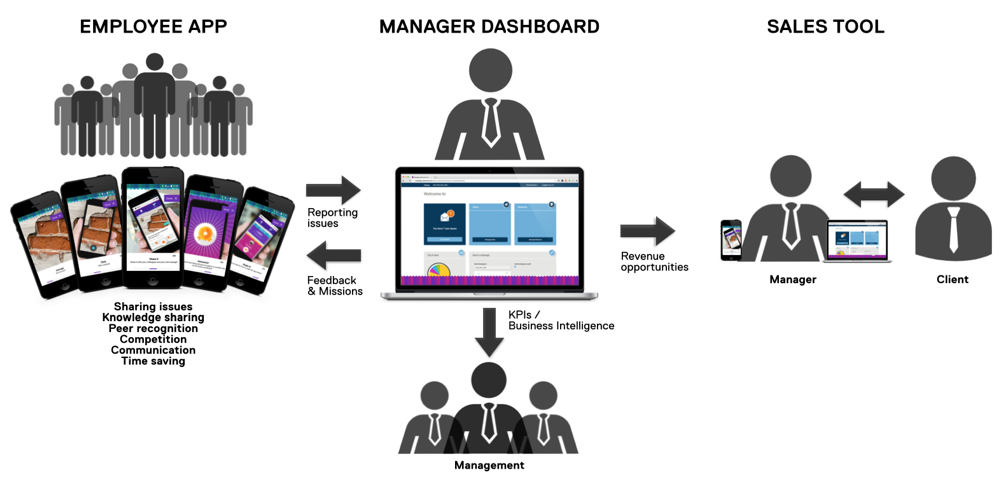

an overview of the Share@ISS concept.

the App tour, the user sees when opening the app for the first time.

3. Results

One of the highly valuable outcomes of the Share@ISS pilot project was the Proof of Concept, which has moved the organisation from imagining to knowing that a gamified mobile application like this one generates positive results on the facilities where it’s being used. Perhaps the most important result was that there was significant pre-post increase in the number of employees submitting ideas for improvements. On average a location experienced an increase of more than 200% of employees being proactive in sharing their ideas for facility improvements. Of 116 relevant users across the pilot site, 94% (111 users) were unboarded (taught to use it) by the end of the 3-month period, 71% of those were using it actively (+5 logins). A total of 916 ideas for improvements were shared (average across sits = 9 per employee) and of the 916 ideas shared, 667 (73%) were the desired proactive behaviour. 249 (27%) were proactive ideas for improvements that were not automatically covered in ISS’ contract with the client, meaning additional revenue opportunities. These numbers are based on the fact that not all 111 users were active users for 3 months; they were gradually joining during these 3 months.

4. The Future

Share@ISS can be viewed as a typical example of consumerisation of IT (consumer IT standards spreading to the business world). Outside work, people get off the sofa to battle their friends on fitness apps, and Facebook is approaching 1.5 billion monthly active users – so why shouldn’t a traditional company like ISS seize the opportunity in integrating these proven motivational formats if they can go hand-in-hand with the core of the business? Indeed, not all work processes or digital business solutions can be turned into a super easy and “fun to use” app, but share@ISS has proven that in some cases, a work process can indeed be gamified and made easy and fun to do. The ethnographic approach ensured that the app was built on already existing intrinsic motivational factors such as the positive social feedback of doing a “good job” and earning recognition from peers and managers. For this reason, the application was not just some add-on to make things fun but at heart a useful tool, which eases the workflow, gamification or not.

During the pilot testing the Orchard team saw that several employees used the social feed to discuss and ask questions around the shared ideas and issues. As a consumer this is obviously not turning heads, since this is how it works on social media. However, as a global company it puts things in a very different perspective as these kinds of companies have traditionally been searching for ways to make knowledge sharing happen. How do you make sure that a great idea in one corner of the world is seen in the other? Internal newsletters, intranets and even newer corporate social media platforms haven’t entirely solved the problem. Perhaps Share@ISS, which combines a useful work tool that you need frequently with a social component and gamification to help drive motivation, could put an end to ISS’ 114 years of struggling with getting knowledge sharing to really work.

Share@ISS Is currently being requested by new accounts within ISS without any PR, and continuous development of the app and program is ongoing. The next step is to extend Share@ISS to facilitate knowledge sharing in general and not just ideas for improvements. The first behavior to investigate and to gamify is: when employees face a new problem or a problem they know but there might be a smarter way to fix: ask!